One of the greatest times to buy stocks was in 1980, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average was at 850. By September of 1987, it was at 2,580, a 235% gain in seven years.

This massive bull market was preceded by 16 years of zero growth — the Dow was at 850 in 1964. By 1980, stocks were extremely undervalued. The price-to-earnings ratio was just 7.39.

When interest rates started falling from 14%, the stock market started to move.

The Raiders

Stocks had so much stored value and were so poorly run that corporate raiders could make millions just by threatening takeovers. It’s where people like Carl Icahn and T. Boone Pickens got their reputations and fortunes.

Pickens owned an oil company called Mesa Petroleum. He saw that a company called Hugoton Production Company was priced at around $5 per barrel of reserve. At the time, a well was deemed profitable at $15 a barrel for wildcatters. The price per barrel was $37. Pickens saw that he could find more oil in a takeover than with a drill rig.

The problem was that Hugoton was 30 times the size of Mesa. You must remember that in the 1980s, board members were sitting fat on perks and salary but didn’t have stock like they do today.

Pickens took out a line of credit and started accumulating shares. Despite buying only 2% of the Hugoton shares on the market, Mesa’s hostile bid drove the market value of Hugoton from $77 million to $137 million in just a few weeks. It wasn’t the first time a hostile takeover bid by Pickens would significantly drive up a company’s value.

Pickens later tried to buy Cities Service Company, which again drove up the share price. The board didn’t want to give up their cushy jobs, so they paid Pickens to go away — a new term, “greenmail,” was created for this practice. Mesa made $31 million on the deal.

This practice of unlocking value from poorly run companies though corporate raiding was perfected by Carl Icahn. He didn’t even borrow the money for his raiding. He had a shady investment bank run by Michael Milken write a “highly confident letter” saying they could get financing when needed. It had zero legal status but was enough…

Icahn used this in a failed attempt to take over Phillips 66 — failed in that Icahn didn’t end up owning the company, but it was quite lucrative for him and the shareholders. It drove the stock from $30 to $55, adding almost $1 billion to the market cap.

The New York Times reported at the time: “Mr. Icahn and his group of investors, who purchased a 7.5 million share stake to start their bid, will be ahead by at least $50 million, according to Wall Street traders.”

Mesa Petroleum had initiated the Phillips 66 takeover (though it was finished by Icahn) and made $89 million. Thus, in the heyday of the corporate raider, stocks were driven higher by the mere idea that a takeover was possible.

Which leads to today’s amusing anecdote.

Our analysts have traveled the world over, dedicated to finding the best and most profitable investments in the global energy markets. All you have to do to join our Energy and Capital investment community is sign up for the daily newsletter below.

In June 1987, a mild-mannered securities analyst by the name Paul David Herrlinger called the Dow Jones News Service from his office in Cincinnati.

He offered to buy out the Dayton Hudson Corporation on behalf of Stone Inc. for $70 a share. The stock shot up $9 to $63, with 5.2 million shares changing hands.

The buyout ended five hours later with an announcement by the Herrlinger family’s attorney. From the New York Times:

”This was not a bona fide offer and there is no such company as Stone Inc.” He said Mr. Herrlinger had a nervous condition and had apparently been hospitalized.

In a telephone interview, Mr. Covatta said Mr. Herrlinger was ”ill,” adding: ”The offer he made is just a symptom of something else – some sort of nervous condition. He’s usually a lovely guy, likes to putter in his garden, but in the last few days he’s been a little hyper, but I don’t know why.”

He added: ”I understand that he is now in the hospital.”

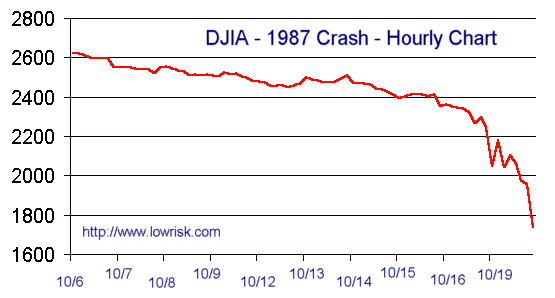

Three months later was Black Monday, when the DJIA fell 508 points, or 22.61%, in a day.

Near the end of every bull market, there is a Paul Herrlinger pointing out the absurdity of the current frenzy. In 1999, it was Henry Blodget raising his price target on Yahoo from $150 to $400, which it hit three weeks later. A few months after that, Yahoo was under $7 a share, and the great dot-com bubble had popped.

Who will be the Herrlinger of this bull market? I don’t know, but keep a weather eye out.

All the best,

Christian DeHaemer

Christian is the founder of Bull and Bust Report and an editor at Energy and Capital. For more on Christian, see his editor’s page.